The Case Against Board Diversity Mandates

BY DR. SIRI TERJESEN, Florida Atlantic University

On behalf of the Club for Growth Foundation

Table of Contents

Overview

Introduction

Myths

Conclusion

Overview

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has proposed and is in the process of developing a number of major changes to corporate governance in the U.S., which will fundamentally alter public companies’ ability to operate according to the best interests of shareholders and other stakeholders.

This policy brief addresses proposals to mandate gender diversity on corporate boards, and presents evidence from decades of research on women on boards and corporate governance.1 In contrast to the frequently cited “business case” for women on boards, the research evidence clearly indicates that quotas and other mandatory guidance for board gender diversity are a net negative to firms, shareholders, and other stakeholders – including the very women whom the initiatives are supposedly intended to help. Specifically, quotas often lead to the appointment of female directors with political or family connections. Evidence from Norway, which enacted the world’s first board gender quota, indicates that several public firms chose to delist from the stock exchange rather than to face growing regulations.

Around the world, leaders in private firms recognize the substantially increasing burden of public regulation, and choose to postpone or never list on the public market. These two strategic responses eliminate the public’s ability to invest in these firms. The brief also highlights the push by institutional investors, rather than the public, for these mandates, and the lack of concrete findings about the impacts of the mandates on financial performance.

Proposed and enacted corporate governance changes are part of a general trend from the Biden administration to enact new legislation and regulations that will slow and stall economic growth. As noted by SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce, the SEC is pursuing a breadth of new “radical rulemakings” that focus on “hot-button matters outside our remit… rush to the aid of professional investors… increase (small and emerging companies) costs and shrink their investor base.”2 Taken together such overreach removes protections of investor and public interest, results in discrimination of certain types of both surface (i.e., aspects of diversity that are easily observed such as gender, race, and age) and deep-level diversity (i.e., traits that are not visible such as socioeconomic status, family upbringing, and religion), and diminishes the U.S.’ ability to maintain a free and open market.

Introduction

Around the world, the desire for gender diversity in corporations led to a focus on the most easily identified and measurable indicator which is also firms’ highest echelon: the corporate board. Most recently, the European Council of the European Union3 issued a directive that at least 40% of non-executive directors (i.e., “outside” directors who do not hold a management position in the firm) should be held by “members of the underrepresented sex” (i.e., women) by 2026. Member states have the option of applying a 33% quota to the entire set of both executive (i.e., “inside” directors who hold a management position in the firm) and nonexecutive directors by 2026. Countries with publicly traded firms which do not comply with the quota will face greater scrutiny of director selection processes. As this new EU law will not apply to countries which have “equally effective legislation before the directive enters force” in 2026, the EU law incentivizes the remaining EU countries that lack board gender quotas to quickly enact more restrictive policies.

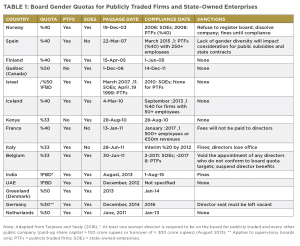

The EU law is the latest evidence of what has been described as an “avalanche” of board gender diversity quotas in Europe, beginning with Norway’s legislation on December 19, 2003, for a 40% gender quota by January 1, 2006, for state-owned firms and January 1, 2008, for publicly traded firms. The latter quota was mandatory for all Oslo Stock Exchange-listed firms, with the severe sanction of delisting from the exchange. Spain followed on March 22, 2007, with a quota of 40% for publicly-traded firms with more than 250 employees, and with the sanction of receiving less public government contracts. Subsequently, eleven other countries and/or regions ratified board gender quotas (See Table 1). Some quotas are described as “hard” when accompanied by sanctions (i.e., delisting, new directors not appointed or paid) while others are described as “soft” when there are few to no sanctions.

In the U.S., the NASDAQ stock exchange issued a requirement that all listed firms must provide a board matrix of director diversity by the latter of August 8, 2022, or the date the firm files its 2022 proxy. The requirement further stipulates that by August 7, 2023, all NASDAQ listed firms must show that there is “one diverse director or provide explanation.” Furthermore, NASDAQ-listed firms with more than five directors must provide evidence of “two diverse directors or provide explanation” by August 6, 2025, for Global Select or Global Markets firms, and by August 6, 2026, for NASDAQ Capital Market firms. While there is no mandate, any NASDAQ-listed company that does not meet the diversity objectives must provide information in a proxy statement, information at the annual shareholder meeting, or on the company website.

To take effect, the NASDAQ required approval from the SEC which was granted in August 2021 by the then Democratic-led commission under a newly appointed Chair Gary Gensler. As noted in a dissenting opinion from SEC Commissioner Elad Roisman,4 the NASDAQ proposal short-changes the SEC’s legal obligations. Roisman spotlights his belief that “diversity and inclusiveness is a worthy goal to have for businesses across our capital markets,” but notes that “a noble goal does not justify short-changing the agency’s legal obligations.” SEC Commissioner Peirce noted that her lack of support for the NASDAQ requirement is grounded in the inconsistency with the Exchange Act and the Constitution: “the Exchange cannot show that its Proposal is consistent with the Exchange Act, and because the Proposal is in fact outside the scope of the Act and contrary to fundamental Constitutional principles.” Specifically, both SEC Commissioners Peirce and Roisman refer to the Securities and Exchange Act (2021)5 which mandates that a clearing agency’s rules “not impose any burden on competition not necessary or appropriate in furtherance of the purposes of” the Act. Id. § 78q-1(b)(3)(I), and that clearing agency rules should be “designed . . . , in general, to protect investors and the public interest.” Id. § 78q-1(b)(3)(F) and “designed to permit unfair discrimination . . . among participants in the use of the clearing agency.” 15 U.S.C. § 78q-1(b) (3)(F).6 As noted by both Commissioners, there is a lack of consistent research findings to support the tenets of the NASDAQ board diversity quota, and the quota would present a burden, fail to protect investors, and result in unfair discrimination.

The NASDAQ ruling was recently declined a review by the court of appeals in the U.S. Fifth Circuit.7

California was the first state8 to mandate that all public firms headquartered in California must have at least one female board member and stipulated fines for noncompliance. Signed into law in 2018, California Senate Bill 826 required California-headquartered listed companies to have at least one female board director by December 31, 2019, and two years later, by December 31, 2021, to have two female board directors if there are five directors and at least three female board directors if there are six or more directors. Subsequently, California’s Assembly Bill 979 in 2020 targeted the same set of California-headquartered, listed companies to appoint board members from “underrepresented communities” which includes anyone who self-identifies as “Black, African American, Hispanic, Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Native Hawaiian, or Alaska Native, or as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender.” The penalties for noncompliance were steep: $100,000 for a first violation, and $300,000 for each subsequent violation, as well as a $100,000 fine for not providing the required information to the state of California. When challenged in court as Crest vs. Padilla, the laws were deemed unconstitutional due to violating the California Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. As summarized by Fortt et al. (2022):

“The court first observed that SB 826 creates a gender-based quota system that “affects two or more ‘similarly situated’ groups in an unequal manner.” After establishing that men and women are similarly situated, the court applied the strict scrutiny test to assess the constitutionality of SB 826. Under strict scrutiny, the state needed to show that SB 826: (1) satisfied a compelling government interest; (2) was necessary to satisfy that interest; and (3) was narrowly tailored to meet that government interest. The court held that the state failed to present sufficient evidence to meet any of the three prongs of the strict scrutiny test.”9

While the unconstitutionality of a board diversity mandate, including the proposed NASDAQ and EU rules, should automatically disqualify such action, a large body of research finds other fundamental downsides to quotas. This paper dispels several commonly cited myths used to justify mandates on board gender diversity, beginning with the myth that women are not being appointed to board leadership positions. This brief highlights the significant organic growth in female leadership in corporations, including the possibility that newly appointed female directors will not assume leadership positions on the board and the subsequent reductions in female leadership in private firms. Another myth is that the general public supports these mandates when, in fact, the mandates are driven by institutional investors such as Goldman Sachs, State Street, Blackrock, and Morgan Stanley. An additional myth is that publicly traded firms will “go along” with the requirements. However, research indicates that quotas lead firms to delist from the public markets or to delay or never go public, thereby harming public interest by preventing the public from being able to invest in these firms. A fourth myth is that mandates lead to the most qualified female directors being appointed. In fact, board diversity mandates often lead to the appointment of family or politically connected female directors. The myth of a “business case” is discredited as a large body of research reveals that board gender diversity is not associated with better financial performance. The brief also provides evidence that board diversity mandates are part of a larger systematic effort to push political and societal changes through the SEC rather than through the correct channels ,which include political and civil institutions.

Myths

MYTH 1

MYTH: Women will not be appointed to corporate boards in sufficient numbers without board diversity mandates.

FACT: There has been substantial organic growth of women directors on publicly traded firm boards over the past few decades, and particularly over the past few years.

Mandatory quotas to appoint a certain share of women to firm boards ignores the substantial organic growth in the representation of women on boards. For example, in 1995 the share of female CEOs, executive officers, and directors of Fortune 500 firms were zero, 8.7, and 9.5 percent, respectively;10 these shares rose to 6, 40, and 30 percent by 2022.11 Moreover, the number of S&P 500 firms led by female CEOs is expected to double by 2025, and organic growth such as the 25.2% share of female directors in Russell 3000 firms reflects the increasing supply of women directors, in part due to the increase in female MBA students and women with significant business experience.12 Elsewhere in the world, countries without quotas, such as the United Kingdom, have almost 40% representation of women directors in the largest firms (i.e., FTSE 100 index).13 Indeed the UK, which lacks any quota, is an example of other non-government mandated initiatives such as targets and mentoring programs which have led to a substantial increase in the organic growth of women on boards. Around the world, successful non-mandatory programs include the Netherlands’ “Talent to the Top” pledge to voluntarily add more women directors and the Australia Institute for Corporate Directors’ mentoring and sponsorship programs paired with training courses.14

One of the unfortunate outcomes of imposing mandatory quotas is that women appointed to boards after the imposition of such a quota face discrimination in that others perceive that their appointments are based on gender rather than talent. The nonprofit Independent Women’s Forum, whose members include many female board members and other leaders, has publicly commented against the NASDAQ ruling: “Requiring certain seats be filled by specific demographic groups will only cheapen their achievements, telegraph that their positions are not merited, and worsen stereotypes and prejudices against these groups.”15 A recent report questions whether newly appointed female directors will serve as leaders, rather than just members, of their boards.16 Many qualitative studies spotlight quotes from male leaders who perceive females may be appointed based on their gender, and not their qualifications, and also from female board directors who do not wish to be perceived as appointed based on their gender.17

A growing stream of research examines the importance of providing equality of opportunity rather than a quotalike focus on equality of outcome. Two separate studies show U.S. states with a history of greater levels of personal freedom and civic engagement and social networks are more likely to have higher shares of female directors on boards. Using U.S. county-level data, Afzali et al. (2022) show that communities with a history of greater levels of social capital (as proxied by civic engagement and social networks) are more likely to have higher shares of female directors.18

Another unfortunate outcome is that board diversity mandates create an artificially high demand for women executive talent in targeted publicly traded firms, with the downside that private firms are less able to retain this talent.119

MYTH 2

MYTH: Publicly traded firms will comply with a board diversity mandate.

FACT: Publicly traded firms may delist, and nonpublic firms may delay or never enter public markets when faced with a board diversity mandate.

The sheer scale of the proposed overreaches will lead firms to reduce their exposure, with one possible response being that publicly traded firms will go private and delist from the U.S. market. The delisting response is hugely detrimental to the public as the average American will no longer have the ability to invest in these companies.

Evidence from Norway indicates that the board gender quota preceded the delisting of several firms from the Oslo Stock Exchange. Among the analyses of large databases, Bøhren and Staubo (2014:152) report:20

“half the initially [gender quota] exposed firms choose to delist, and that this exit propensity is driven by firm characteristics. This result suggests that the regulation is costly for firms in general, more costly for some firms than for others, and that even non-exiting firms may end up with suboptimal boards because the benefit of keeping their exposed organizational form exceeds the inherent cost of forced gender balance.

The aforementioned study by Ahern and Dittmar (2012) reviews evidence from Norway that the number of publicly listed companies decreased 23% and that Norwegian firm incorporations increased four times, concluding that “firms most affected by the quota chose to avoid the law through a change in incorporation.” and “firms are more likely to delist if they have a younger board with less CEO experience” (2012: 49, 52).

MYTH 3

MYTH: The general public supports board gender diversity mandates.

FACT: Institutional investors, rather than the general public, have been strongly advocating for gender diversity mandates.

Proponents of board gender diversity mandates inaccurately suggest broad support from the general public, including shareholders in publicly traded firms. In fact, most demands for board gender diversity directives come from institutional investors who represent individual shareholders, such as those who own shares through a mutual fund. These institutional investors then vote the share proxies. Examples here include Morgan Stanley which in 2017 began “encouraging” analysts to consider gender scores for their investments, BlackRock’s 2018 expectation that its portfolio companies have at least two women directors, State Street Global Advisors’ statement that it would vote against any board that is allmale, and Goldman Sachs’ vow to only underwrite IPOs with one director from a “traditionally underrepresented group”.21 The Institutional Shareholder Services adopted a policy of recommending against all-male boards in 2021, and Glass Lewis decided to recommend against voting for boards with fewer than two women directors beginning in 2022.22 (Breheny et al., 2020).

MYTH 4

MYTH: Board diversity mandates lead to the appointment of female directors who are the most qualified.

FACT: Board diversity mandates lead to the appointments of female directors who have family or political connections.

There is tremendous quantitative and qualitative evidence that a push for greater representation of women on boards leads to appointments of women that reflect nepotism and political connections. For example, when France faced a board gender diversity quota, almost 25% of newly appointed female directors were family members.23 One striking example is French manufacturer of military aircraft and business jets Dassault Aviation’s appointment of Nicole Dassault, wife of the controlling shareholder. Other female board appointments in France spotlight the role of political and family connections such as former First Lady Bernadette Chirac’s appointment to the board of luxury conglomerate LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton), as well as the appointments of the wives of the former Minister of Labor and former Minister of Defense to the boards of luxury conglomerate Hermès and broadcaster Canal Plus. Recent evidence for India indicates a preference for “celebrity” female directors.24

A more recent example in the U.S. are the many women who served in the Obama administration who have been appointed to corporate boards, such as former Senior Advisor to President Obama and Director of the Office of Public Engagement and Intergovernmental Affairs Valerie Jarrett who joined the boards of education technology 2U and service mobility Lyft, and former Secretary of Health and Human Services Sylvia Burwell who joined the boards of paper-based consumer products conglomerate Kimberly-Clark and health insurer GuideWell. These appointments are part of a well-documented trend to appoint politically connected directors.25

MYTH 5

MYTH: Firms with more female directors perform better financially.

FACT: There is no consistent, and often a negative relationship, between greater presence of female directors and improved financial performance.

The extant literature highlighting the benefits of board gender diversity mandates often cites inaccurate research, or cherry picked findings. For example, the existing literature frequently references the “business case” of enhanced financial performance for more gender diverse boards. This research often uses market capitalization as a measure of financial performance. Market capitalization is calculated as the number of shares times the price per share, and is essentially a measure of firm size as firms with greater market capitalization have more sales and more employees. These firms also have larger boards, and a larger sized board is nearly always correlated to a greater share of women on the board.26 There are also mixed results in studies of the relationship between board diversity and other measures of firm performance such as Tobin’s Q, stock price, profits, and return on assets.

TOBIN’S Q: A seminal study of quotas, by Ahern and Dittmar (2012) of 166 Oslo Stock Exchange listed firms from 2001-2008, reveals a negative relationship between the appointment of women and firm value (measured as Tobin’s Q: the sum of total assets and market equity less common book equity divided by total assets).27 Specifically, every 10% increase in female directors results in a 12.4% decline in Tobin’s Q.

STOCK PRICE: Amongst the many papers exploring the link between stock price and performance, Nygaard (2011) explores Norwegian firms facing the quota, and reports positive returns only amongst firms with low information asymmetry- that is publicly available information to effectively monitor outside directors.28 Nygaard (2011) also notes that the positive returns might not be explained by the boards’ female director presence, but rather by the boards’ greater proportions of external directors. The afore-mentioned Ahern and Dittmar (2012:1) study concludes that “the constraint imposed by the quota caused a significant drop in the stock price at the announcement of the law” (2012:1). Specifically, they report that once the quota law was announced, firms with no female directors lost over 3 percentage points compared to firms with at least one female director. They assert that firms with the largest constraints lost 20% of their value.

PROFITS: Matsa and Miller (2013) examined publicly traded Norwegian firms impacted by the quota (ASA: Allmennaksjeselskap) compared to private (AS: Aksjeselskap) companies in the period of pre-quota voluntary compliance (2003-6) compared to mandatory compliance following the enactment of the quota (2006- 9). They report that firms that faced the quota had fewer workforce reductions and higher labor costs and employment levels, resulting in short-term profits. These effects were strongest amongst firms that did not have any female directors pre-quota. Matsa and Miller (2013:1) conclude that “the boards appear to be affecting corporate strategy in part by selecting likeminded executives.”29

OTHER ACCOUNTING DATA: Financial performance can also be measured based on return on assets (ROA) which is calculated as the ratio of net income over total assets, as well as considering operating revenues (all funds earned through the business) and operating costs (expenses incurred from running the business). A study of Norwegian firms’ accounting data for 2003-7 compares non-finance public limited companies (PLCs) to ordinary limited companies (LTDs), finding no differences in ROA or operating revenues and costs due to the quota.30 The authors Dale-Olsen et al. (2013: 129) conclude:

“the short run impact of the reform on economic firm performance is negligible. This implies either that the short-run influence of boards is small, or that newly recruited women do not bring along markedly different resources and perspectives compared to the men that they replace. Furthermore, these results do not seem to be driven by selection of firms into the treatment group (PLCs) and the control group (LTDs). In the long run, the effects might be different.”

A recent meta-analysis of 140 studies also reports mixed results.31 Moreover, many studies are plagued with data limitations, selection issues, and causal inference.32 For example, many studies fail to account for endogeneity in the data—that is, an explanatory variable is correlated with the error term. Two recent studies explore the impact of a board gender diversity quota and account for endogeneity. A comparative study of Scandinavian firms reports that Norway’s mandatory 40% board gender quota significantly adversely affects firm performance relative to similar firms that did not face a quota in Sweden, Denmark, and Finland.33 A study of Spain’s quota reveals that firms that are more subject to the sanction (in this case, reduced likelihood of winning public contracts) are more likely to comply, but even those firms that comply are not more likely to receive more public contracts.34

MYTH 6

MYTH: Once a board diversity mandate is in place, firms can go back to focusing on other issues.

FACT: Board diversity mandates are just one step towards unconstitutional and detrimental corporate governance overreach, and are an excessive government intervention in firm operations.

Board gender diversity mandates are the outcome of left-leaning government coalitions and a legacy of path dependent gender equality initiatives in public policy, including corporate governance codes. These mandates will lead to greater unconstitutional and detrimental overreach in other areas. For example, there are demands that the SEC mandate greater human capital accounting and climate-related disclosures . As noted earlier, board diversity quotas for corporations are unconstitutional, and represent excessive government intervention in firm governance.

Conclusion

As the U.S. and many other economies around the world slide into an economic slowdown and recession, the priority of the SEC, EU, and other governments should be to help firms succeed, rather than to introduce new obstacles in the form of unnecessary and stifling legislation and regulations. The need to focus on progrowth policies is particularly prescient given recent declines in labor market productivity. Board diversity mandates are unconstitutional and a form of unnecessary regulation that can lead to greater bureaucracy and other burdens on firms.

In addition to the unconstitutionality and unnecessary burden of board diversity mandates, a large body of research reveals substantial shortcomings which this brief has reviewed. Female board directors’ significant organic increase in representation does not support the need for mandatory policies. Moreover, mandatory board diversity does not lead to the appointment of the most qualified directors, but often also those directors with family or political connections. When facing board diversity mandates, firms may choose to delist, or private firms may delay or never seek public equity. While such mandates are often described as publicly supported, the majority are driven by institutional investors. This brief also outlined the mixed and often negative “business” case in terms of firm financial performance. Worryingly, greater board diversity is not likely to yield better corporate governance processes, and is more likely to be part of a larger effort to push the imposition of further unconstitutional changes.

Endnotes

- Among many reviews: Terjesen, S., Sealy, R., & Singh, V. 2009. Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 337-320 ,)3(17. Terjesen, S., & Sealy, R. 2016. Board gender quotas: Exploring ethical tensions from a multi-theoretical perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 65-23 ,)1(26.

- Peirce, H. 2022. Rip current rulemakings: Statement on the regulatory flexibility agenda. https://www.sec.gov/news/statement/peircestatement- regulatory-flexibility-agenda-062222

- European Union Council. 2022. Council approves EU law to improve gender balance on corporate boards. October 17. https://www. consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/17/10/2022/council-approves-eu-law-to-improve-gender-balance-on-company-boards/

- Roisman, E. 2021. Statement on the Commission’s order approving exchange rules relating to board diversity August 6. SEC. https:// www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/roisman-board-diversity

- Securities and Exchange Act. 2021. Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. Updated to 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/ COMPS-1885/pdf/COMPS-1885.pdf

- Roisman also notes that these arguments were made in Susquehanna International Group, LLP, et al. v. SEC (DC Cir.) (Aug. 2017 ,8), https://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/88E0BCE087554C0B8525817600508F2A/$file/1687695-1061-16.pdf.

- https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/15/11/2023/fifth-circuit-declines-to-review-secs-approval-of-nasdaqs-board-diversity-rule/

- California’s regulations were quickly followed by Washington (SB 2020 ,6037). Other states pursuing legislation include: Colorado (H J. Res. 2017 ,1017-17), Massachusetts (S. S. Res. 2015 ,1007), and Pennsylvania (H Res. 2017 ,273) passed non-binding resolutions encouraging board diversification; Maryland (HB 2019 ,1116), Illinois (HB 2019 ,3394), and New York (SB 2019 ,4278) established mandatory disclosure of board gender diversity. Hawaii (SB 2021 ,193), Michigan (SB 2021 ,64), and Oregon (HB 2021 ,3110) have gender quota statutes in the legislature.

- Fortt, S., Huber, B., & Vaseghi, M. 2022. California gender board diversity law is held unconstitutional. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/12/06/2022/california-gender-board-diversity-law-is-held-unconstitutional/

- Catalyst. 1995. Quick take: Women on boards.

- Catalyst. 2022. Women in the U.S. workforce. https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-the-united-states-workforce/

- Morrison, R., & Terjesen, S. 2022. Shaky case for mandating gender diversity on corporate boards. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek. com/shaky-case-mandating-gender-diversity-corporate-boards-opinion-1647102

- FTSE Women Leaders Review. 2021.

- Branson, D.M. 2012. An Australian perspective on a global phenomenon: Initiatives to place women on corporate boards of directors. Australian Corporate & Securities Law Review.

- Independent Women’s Forum. 2020. IWF public comment regarding proposed rule change allowing Nasdaq to create gender and diversity quotas for listed companies. SR–NASDAQ–082–2020

- The Diligent Institute. 2020. A few good women: Gender inclusion in public company board leadership. March.

- Wiersema, M., & Mors, M. 2016. What board directors really think of gender quotas. Harvard Business Review, 14(November), 6-2. Jonsdottir, T., Singh, V., Terjesen, S., & Vinnicombe, S. 2015. Director identity in pre-and post-crisis Iceland: Effects of board life stage and gender. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 594-572 ,)7(30.

- Afzali, M., Silvola, H., & Terjesen, S. 2022. Social capital and board gender diversity. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 481-461 ,)4(30.

- Tyrowicz, J., Terjesen, S. and Mazurek, J. 2020. All on board? New evidence on board gender diversity from a large panel of European firms. European Management Journal, 645-634 ,)4(38.

- Bøhren, Ø., & Staubo, S. 2014. Does mandatory gender balance work? Changing organizational form to avoid board upheaval. Journal of Corporate Finance, 168-152 ,28. Gray, S., Harymawan, I., & Nowland, J. 2016. Political and government connections on corporate boards in Australia: Good for business? Australian Journal of Management, 26-3 ,)1(41. Okhmatovskiy, I. 2010. Performance implications of ties to the government and SOEs: A political embeddedness perspective. Journal of Management Studies, -1020 ,)6(47 1047.

- Froehlicher, M., Knuckles Griek, L., Nematzadeh, G., Hall, L., & Stovall, N. 2021. Gender equality in the workplace: going beyond women on the board. S&P Global. February 5. https://www.spglobal.com/esg/csa/yearbook/articles/gender-equality-workplace-going-beyondwomen- on-the-board

- Breheny, B. V., Gerber, M.S., Grossman, R.J., Olsham, R., Birndorf, S., & Grady, B.M. 2020. ISS and Glass Lewis release. December 7. Skadden. https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/12/2020/iss-and-glass-lewis-release.

- Singh, V., Point, S., Moulin, Y., & Davila, A. 2015. Legitimacy profiles of women directors on top French company boards. Journal of Management Development, 820-803 ,)7(34.

- Bhardwaj, S. 2021. Corporate governance and gender diversity in India. PhD Thesis. Federation University.

- Lester, R.H., Hillman, A., Zardkoohi, A., & Cannella, A.A. 2008. Former government officials as outside directors: The role of human and social capital. Academy of Management Journal, 1013-999 ,)5(51.

- Terjesen, S., Sealy, R., & Singh, V. 2009. Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 337-320 ,)3(17.

- Ahern, K.R., & Dittmar, A.K. 2012. The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 197-137 ,)1(127.

- Nygaard, K. 2011. Forced board changes: Evidence from Norway. NHH Dept. of Economics Discussion Paper, (5).

- Matsa, D.A., & Miller, A.R. 2013. A female style in corporate leadership? Evidence from quotas. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 69-136 ,)3(5.

- Dale-Olsen, H., Schøne, P., & Verner, M. 2013. Diversity among Norwegian boards of directors: Does a quota for women improve firm performance? Feminist Economics, 135-110 ,)4(19.

- Post, C., & Byron, K. 2015. Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 1571-1546 ,)5(58.

- Adams, R.B. 2016. Women on boards: The superheroes of tomorrow? The Leadership Quarterly, 386-371 ,)3(27.

- Yang, P., Riepe, J., Moser, K., Pull, K., & Terjesen, S. 2019. Women directors, firm performance, and firm risk: A causal perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 101297 ,)5(30.

- De Cabo, R.M., Terjesen, S., Escot, L., & Gimeno, R. 2019. Do ‘soft law’ board gender quotas work? Evidence from a natural experiment. European Management Journal, 624-611 ,)5(37.